A Detailed Account

Being a gay teenager — anytime, anywhere — has never been easy. But few have had to pay so terrible a price as has Bernard Baran, of Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

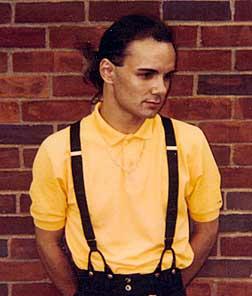

Pittsfield, a working-class town of about 50,000 in western Massachusetts, is near the New York border. Baran was born there on May 26, 1965, the youngest of three children. Baran’s father left when Bernie was only three, but Bertha, Baran’s mother, held the family together. She might have had to melt garbage bags to patch the holes in her own shoes, but her children didn’t go without if she could help it. Bernie was her baby, and she held him back from school for an extra year.

When very young, Bernie realized that he was gay. This was hard for his mother to understand at first, but she came to accept it because she loved her son. But school was not easy for Bernie. Although he is not effeminate, his gentleness advertises vulnerability. In 1981, after completing 9th grade, and having just turned 16, he quit school.

He enrolled in the CETA job-training program, and was placed first at the Red Cross, and then later at the Boy’s Club, where he did maintenance work and sat at the front desk answering the phone and giving out badges. On January 7, 1983, he was assigned to a Pittsfield daycare, the Early Childhood Development Center (ECDC) as a Teacher’s Aide. Bernie liked kids, and he’d had a lot of experience babysitting — for his Aunt Sandy, for his sister, and for his own little brother, who’d been born around the time Bernie left school.

At ECDC, Bernie was well liked by children, staff, and teachers. On August 1, 1983, Baran was hired directly by the school. His performance was good to excellent. He went through a period in the spring of ‘84 when he was often late, but corrected the problem after being placed on probation. Some thought he spent a little too much time in the teacher’s lounge on the third floor, taking cigarette and coffee breaks. But he was good with the kids and he never gave anyone the slightest reason for suspicion. No parent ever complained — that is, before the trouble started on October 4, 1984.

Baran was also happy in his personal life. He had come to love another young man, a few years his senior. Ricky was a musician, played in a band, and he taught Bernie how to do sound. Although Bernie lived at home with his mother, he often spent nights at Ricky’s — especially after he’d been warned about coming in late. (Ricky lived much closer to ECDC than did Baran’s mother.)

The Accusing Family

I don’t know how much longer I can hold on for. I have spent 15 years of my life locked away for something I never did and after a while you start to lose all hope … I fear the hope that others bring into my life because I’m always left alone in the pain.”-Bernard F. Baran, Jr.

March 3, 1999

Mr. Baran does not live in a nice world. Nor do we. There is work to be done. And he is doing it. To the philosopher, Mr. Baran, with his bare hands, is re-shaping civilization right before our very eyes.

The more interesting things about Mr. Baran are the kind of man he has made of himself, the qualities of people he has drawn in, and his extraordinary courage and stamina in the face of the circumstances of his life, unimaginable to most of the rest of us. His contribution to society is vast, and still to be measured, contemplated, absorbed. I hope he lives long enough to be acknowledged for it.

–Baran Supporter William Dion

The destruction of Bernard Baran’s life began with an ECDC pupil who was a much troubled little boy from a very troubled family — Peter Hanes. (All children’s names have been changed.) What happened, of course, was not Peter’s fault. Peter was born November 6, 1980, to Julie Hanes, who was then 19. Julie had left her own troubled home at 15, after her mother had thrown a knife at her and had beaten her, breaking several ribs, at a family Fourth of July picnic. Peter’s father was James Hanes, who left Julie when Peter was two or three weeks old. Julie immediately began dating James’s cousin David, who soon moved in. David had a serious drug problem, and before long, so did Julie. Both Haneses were often in and out of rehab. (Julie was twice reused admission to detox.) Peter was sometimes left with Julie’s mother at these times. Julie often showed up at emergency rooms suffering from drug overdoses. She mainlined cocaine, but also used morphine, Dilaudids, Nembutals, Seconals, and Percodan. David sometimes stole the paregoric that Julie’s pediatrician prescribed for Peter’s baby brother. Julie would steal syringes from the office of this same doctor.

David was very abusive physically. He once held Julie from a second-story window by her ankle. At the suggestion of the Department of Social Services (DSS), Peter was enrolled at ECDC in December of 1982, even though he was below their usual age limit. The boy sometimes came to school with bruises. (Peter was not placed in the room where Baran worked until 9/21/83.) On March 29, 1983, David Hanes allegedly stabbed himself in his own heart and had to have open-heart surgery as a result. In May of 1983, Julie gave birth to a second son, George. (Julie’s next live-in boyfriend also allegedly stabbed himself in the chest.) Peter (and later George) were sometimes placed in foster care, but they were always shortly returned to their abusive home. (For more information about Hanes family life, click here.)

Peter was a big problem at ECDC from the beginning. He swore, had mood swings, hit other children, threw things around the room, threw rocks and other things at other children, pulled their hair, kicked them, stepped on and broke toys, slapped teachers, screamed, threw food about the room during meals, threw a fork at a teacher, climbed up on shelves, threw temper tantrums, defecated in the play patch, pushed another child off a chair, and tried to remove fish from the fishbowl. He wet himself almost every naptime. Julie had frequently been asked to send in a change of clothes for Peter, but she seldom did. Thus Peter was often changed into the spare dry clothes that ECDC kept on hand, and sometimes Bernie Baran changed him. By June of ‘84, ECDC was ready to expel Peter. But they decided to give him another chance and moved him from room #1 (Baran’s room) to room #4. In July, Baran began splitting his time between the two rooms. In August, Julie tried to get into drug rehab one more time.

The Cultural Context

While all of this was going on, America was it the midst of a great social upheaval. Cultural anxieties about sex were at fever pitch. The leaders of the conservative backlash against 60s sexual liberation gained political power with the election of Ronald Reagan. Sensing a shift in public sentiment, liberal leaders, including people active in the women’s and gay movements, also moved to the right.

At first, the modern women’s movement had been concerned with the historical and demonstrably unfair treatment women had received in America. Another legitimate concern that soon emerged was the callous treatment by a male-dominated legal system of women who had been raped or otherwise sexually abused. When the battle for social and economic justice went badly — for example, with the defeat of the Equal Rights Amendment — feminism focused on the notion that women were the victims of male sexual power and transgressions. Men sexually victimized women (and children) not only by what they did, but also through expression, especially through the production and consumption of pornography. As a result civil libertarians — including the ACLU — weakened or even abandoned their historical commitment to presumption of innocence, the rights of the accused, due process, and the First Amendment. The gay movement, closely aligned with feminism, followed suit.

Our culture has always been homophobic. Gay men are considered a threat to children — to little girls as well as little boys. While the gay movement of the 70s helped some people to view gay men and lesbians as human beings, others instead increased their hatred, repelled by the flamboyance and increased visibility of what they considered unnatural sexual minorities. In 1978, former Miss America runner-up Anita Bryant unleashed a national homophobic movement called “Save Our Children.” In Revere, Massachusetts, around this time, police discovered that two male teenage hustlers were using a gay man’s apartment to turn tricks. The local media, including the Boston Globe, announced the discovery of a major child sex ring. Hotlines were set up and people were encouraged to make anonymous tips to the police. During this panic, according to Debbie Nathan, “a Boston-area child protection researcher, psychiatric nurse Ann Burgess, began elaborating the totally unfounded idea that gay men were organizing into international ’sex rings’ to fly boys around the world, distribute them among networks of men, and make child pornography. This notion enjoyed a lot of currency in the Justice Department and police departments during the Reagan years. Burgess and one of her students, Susan Kelly (an interrogator in the Amirault case), went on to promulgate the belief that ’sex rings’ had extended to Satanist groups operating in daycare centers.”

Daycare centers proliferated in the early 80s as more women entered the workforce, more from economic necessity than incitement by the women’s movement. Gender roles were breaking down as women entered male-dominated professions, and men started doing childcare and other forms of “women’s work.” This gender-role breakdown caused great alarm in conservative, especially religious conservative, circles. But non-conservative women were also anxious and guilty about entrusting their small children to the care of strangers — especially to the care of strange men.

The intense fear of gay men was furthered inflamed at the time because of the outbreak of the AIDS epidemic. Gay men were viewed as diseased people, physically as well as mentally — the carriers of horrible, uncontrollable, incurable disease.

The Daycare Panic

Given all of this, it is not surprising that the daycare panic erupted and raged out of control for so many years. Homophobia was the hidden motor that drove the panic and the prosecutions. Most of these cases began with someone from a highly dysfunctional home accusing a male of abusing a little boy. The best known of the daycare cases is the McMartin, or Manhattan Beach case, which erupted in August of 1983 when an alcoholic, paranoid schizophrenic woman named Judy Johnson decided that the bottom of her pre-verbal two-year-old son looked red and accused Ray Buckey, a 25-year-old man who worked at the McMartin daycare center. By March of 1984, 208 counts of child abuse involving 40 children were laid against Ray Buckey, his mother Peggy Buckey, his grandmother Virginia McMartin, and four other teachers. The case finally ended in 1990, without a single conviction on any count. It was the longest and most expensive trial in history.

The McMartin case spawned copycat cases all over the country. In Malden Massachusetts, on September 5, 1984, the police arrested Gerald Amirault, a worker at the Fells Acres Day School. Later Gerald’s mother, Violet, and sister, Cheryl, were also arrested. Gerald was convicted in July of 1986. He remains in prison. Violet (now deceased) and Cheryl were convicted in June of 1987. Cheryl was granted a new trial in June of 1998. This ruling, however, was appealed to the Supreme Judicial Court, which on 18 August 1999 unanimously ruled that Cheryl must return to prison, because “finality” is a more important consideration than mere justice. (When it came down to actually sending Cheryl back, however, Middlesex District Attorney Martha Coakley balked and finally offered a deal. Coakley agreed to allow the judge to revise-and-revoke Cheryl’s sentence to time served, provided Cheryl agreed to Coakley’s terms, which included Cheryl relinquishing her First Amendment right to discuss her case on television. Prosecutors will go to great lengths to keep the truth from the public.)

The McMartin case was major national news, and the Amirault case was major news in New England. The news coverage was extremely biased, and most people assumed that all of the accused were guilty. (In January, 1986, a telephone poll taken in the Manhattan Beach area showed that 97% of those with an opinion thought Ray Buckey was guilty and 93% thought that Peggy Buckey was guilty.)

(For an excellent account of the daycare hysteria, read this article by Dr. David Lotto, a psychotherapist practicing in Pittsfield who researched the phenomena because of his concerns with the Baran case.)

The First Accusation

Right around the time Gerald Amirault was arrested, David Hanes called ECDC to complain that Bernard Baran was a homosexual, and Hanes objected to Baran’s being allowed to work in childcare. (For more information about this incident and about the Hanes’ general feelings about gay men — in Julie’s sworn deposition — click here. David Hanes eventually came to doubt Baran’s guilt. Click here for excerpts from his deposition. The two depositions reveal much about the moral character — or lack thereof — of the family that destroyed Bernard baran’s life.) No further accusation was made at that time. A few weeks later, on Monday, October 1, 1984 Peter Hanes was removed from ECDC. On Friday, October 5, David Hanes called the Pittsfield Police and said that his son “had come home from school yesterday with or after examination had blood on or coming out of the end of his penis.” (from the police report) This was supposedly discovered while Julie, David, or both were giving Peter a bath on the evening of October 4. During a civil suit tried in 1995, Julie Hanes admitted under oath that she actually “didn’t see any blood because he was in the water, but he said it hurt.” Allegedly, Peter was asked if anyone had touched him there, and Peter had said, “Bernie.” Given that Bernie was considered by the Haneses to be a bad person (for being gay), and that Peter almost certainly knew that Bernie was supposed to be bad, it’s quite possible that Peter would have volunteered Bernie’s name even without prompting. It’s also quite possible that the bathtub incident never occurred — given the fact that Julie Hanes’s inconsistent and self-serving testimony at the later civil trial destroyed her credibility and also given the fact that David Hanes eventually came to doubt Baran’s guilt. The bathtub story first emerges at trial, in Julie Hanes testimony. This occurred not long after Peter accused one of Julie’s boyfriends of sexually abusing Peter in the bathtub.

According to information unearthed for the civil trial, David Hanes, on October 4, had called his drug handler at the police department. (Both David and Julie were drug informants by this time.) The police phoned the Haneses several times that evening, but were told by a baby sitter that they had gone out to the movies.

The next morning, David Hanes called the police and Julie took Peter to see their pediatrician, Dr. Jean Sheeley. According to Julie’s civil testimony, Sheeley saw nothing wrong with Peter’s penis — no cuts, bruises or abrasions. Sheeley herself testified at Baran’s trial that she did a urinalysis and eliminated the possibility of internal bleeding. Sheeley also tested Peter for gonorrhea.

The Second Accusation

At 1:30 p.m. on October 5, Detectives Collias and Beals went to ECDC. According to the police report, Janie Trumpy, the new ECDC Executive Director, checked Peter Hanes’ file and informed the detectives of David Hanes’ complaint about Baran’s homosexuality around the beginning of the school year. A Sue Eastland (actually Eastman) had taken the complaint. (At the trial, Trumpy testified that there was no complaint on file, that she didn’t know who Sue Eastman was, that there’d been some sort of complaint over the summer about Baran, relayed to her by Lynn Witter, but that Trumpy didn’t know who had made the complaint. It might have helped Baran had the jury known that the Haneses considered Baran a sexually dangerous person weeks before Peter Hanes’ alleged disclosure. For a more complete account of the discrepancies between the police report and Trumpy’s testimony, click here.) Trumpy agreed that Baran wouldn’t be left alone with children.

In any case, it was ECDC policy never to leave any adult alone with children. In each room, there was a Head Teacher, an Assistant Teacher, and a Teacher’s Aide. In addition to the paid staff there were CETA workers, volunteers from Miss Hall’s school (a nearby private secondary school), and a nearly blind volunteer named Katie Donahue. If teachers or aides had to be absent, they were covered. Bathrooms adjoined classrooms and bathroom doors were always kept open in case toddlers needed assistance. It was an environment that provided few opportunities for a child molester.

While Baran was not told that he was under investigation, word among the ECDC staff spread quickly. One person who heard was Carol Bixby, the ECDC Center Coordinator and a former teacher. That evening, Carol called her friend, Judith Smith, an ECDC board member. (According to Baran, Smith is also a self-identified survivor of sexual abuse, but they weren’t able to get that on the record at the trial.) The Smiths had a three-year-old daughter named Gina, who had been a student at ECDC. She had been in Baran’s room from April of ‘84 until she left the school in mid-July. During this time, she attended ECDC 3 days a week, from 8:30-12:30. Baran was in this room from 8:30 until 10:15, then left for break and returned to work in another room. Thus Gina and Baran were in the same room only about five hours a week, and during the busiest part of the day. Most of this time slot was taken up by breakfast.

The Smith household was much different from the Hanes’. Judith and her husband were resident faculty at Miss Hall’s school, a private secondary school. Judith taught ceramics and was the activities director. Her husband headed the art department. Besides Gina, the Smiths had a five-year-old and a 17-month-old infant. After the phone call from Bixby, Judith immediately began interrogating Gina. Mrs. Smith specifically asked Gina about Bernie and whether Bernie ever “touched her in a funny way.” Gina said she and Bernie played the “Bird’s Nest Game,” sometimes in her hair, sometimes in Bernie’s hair. Smith asked if Bernie ever touched her fanny, and Gina allegedly said that Bernie touched her “privies” sometimes. Smith immediately called Janie Trumpy, who told her that Smith should call the police because Gina wouldn’t make something like that up. (Subsequent research — by Stephen Ceci, Maggie Bruck, and others — has shown that young children frequently produce such “accusations” when subjected to suggestive questioning.)

Smith called Police Captain Dermody at his home. (Smith was a friend of Dermody’s wife.) Dermody called the station and asked that detectives be sent to the Smith residence. The detectives called Brian Cummings of DSS, who went with Detectives Winpenney and Eaton. They arrived at the Smith home at 10:50 p.m. Upon questioning, Gina again said that Baran had touched her once on the “privies.” And she again mentioned the Bird’s Nest Game. Gina said that Bernie never touched her fanny. Gina wasn’t interested in talking in front of the policemen, so Smith took her daughter out into the hallway, and then returned to explain what Gina had disclosed.

Gina said that Baran one day had found a bird’s nest, with a dead baby bird still partly in its shell. Baran allegedly said that if the “make believe” or “pretend” police found out, they would come and take the bird away, and that would upset the bird’s mother. (Gina was a most imaginative child, and pretend was one of her favorite words.) Baran never found a dead baby bird while at ECDC, although the janitor once found a dead bird in a bathroom and many of the kids knew about that. Baran did sometimes read to the children a Dr. Seuss book about a bird who goes looking for his mother. The book has an illustration of a policeman in it. Stories about mother separation can cause anxiety in a three-year-old. Gina would go on to create — with much help from the “investigating” adults — the most elaborate (and bizarre) of the tales of abuse.

Smith also said that Gina talked about the “Touch Game.” Baran allegedly put his finger in Gina’s ears, eyes, nose, fanny, and everything else. But Gina was only allowed to touch Baran’s neck. Smith asked Gina if Baran had ever wanted Gina to touch his penis, and “Gina said yes and pointed to her inside of her foot.” Smith took this as confirmation.

The second accusation on the same day convinced the police of Baran’s guilt. While the first police report is labeled “Possible Child Abuse” and contains the phrase, “just in case there is something to this complaint,” the report on Gina Smith is labeled “Indecent A&B of Child Under 14 yrs.” And, like all subsequent police reports in the case, it expressed no skepticism whatsoever.

Hysteria Spreads Like Wildfire

From that point on, the Baran case was a runaway train. He was arrested the next day, a Saturday. Baran denied everything, answered all questions freely, and waived his rights because he had nothing to hide. On Sunday, his mother bailed him out and Baran enjoyed a couple more days of freedom. Those were the last days of freedom he enjoyed — they in fact might turn out to be the last free days of his life.

On the day when Baran was arrested, the Haneses brought Peter into the police station. After a tour of the police station, Detective Beals questioned Peter while Peter sat on Beals’ lap. Peter said that Bernie made his pee pee hurt, made his pee pee feel good, and made his pee pee go away. At one point, Peter said that Bernie made it bleed. When asked if Bernie asked Peter to touch him, “he became offensive to the question and became angry and told us no in no uncertain terms.”

That evening, the Smiths took Gina first to the police station, where detective Eaton gave her a badge, and then to the DA’s office. Jane Satullo, a psychotherapist from the Rape Crisis Center interviewed Gina, and the interview was videotaped. Satullo used anatomically correct dolls, which were frequently used at the time but are now seldom used because research by Ceci, Bruck, and others has shown that the use of these dolls mainly produces false accusations. Gina put her finger in the doll’s openings (vagina and rectum), supposedly showing what Baran had done to Gina. When asked about the Bird’s Nest game, Gina wanted to phone Bernie to make sure it was all right to tell about it. After they only allowed Gina to make pretend phone calls, Gina said she had to go to the bathroom two times, and taping ended for the day.

The next day, it was Peter Hanes’ turn to be interviewed by Ms. Satullo. Satullo gave Peter male and female dolls. After Peter undressed the male doll, Satullo asked him what the penis was, and Peter replied “his bone.” When asked if someone touched his pee pee, Peter replied Bernie. When asked how Bernie touched him, Peter grabbed his crotch. But, according to the police observer, Peter didn’t much want to talk about his pee pee or Bernie. “He seemed to be trying to ignore the subject,” stated the report. Peter went to the bathroom half an hour into the interview. Another half an hour later, Satullo terminated the taping.

The next day, Monday, October 8, ECDC officials, police, and social workers met to prepare for a meeting with parents. That same day, Judith Smith took Gina to see Dr. Sheeley. Gina had a checkup in July, right after she was taken out of ECDC, and no problems had then been found. This time Sheeley did a near microscopic examination of Gina’s rectum and vagina. She found ruptures of Gina’s hymen — two small posterior tears and one large (1-2 millimeters, or about 1/20th of an inch) well-healed anterior tear. Sheeley believed that these tears, especially the larger one, were consistent with full penetration by an adult penis or several adult fingers. (During the trial, while Gina was waiting to testify, Judith Smith told a volunteer from the Pittsfield Rape Crisis Center that Gina had “suffered severe medical damage.”) Sheeley also tested Gina for gonorrhea, but the tests came back negative. While at the doctor’s, Gina said that Bernie had touched her, and also that he had touched her with his penie and his mouth. Gina said it hurt her, and also said something about Bernie’s pretend worm, which Smith at the time interpreted as his penis. Gina also said that there had been blood on her privies, but that Bernie had cleaned it up. Gina said someone else had seen this happen, and Smith asked if it might have been Eileen (Gina’s Assistant Teacher). Gina said yes, it was. Smith, in her statement noted that by mentioning Eileen, Smith was “putting a name in her (Gina’s)] head.” It seems never to have occurred to Smith that from the first she had put Bernie’s name in Gina’s head.

Smith continued to interrogate Gina. Before making her statement on October 11, Smith had decided that the “pretend worm” was ejaculate. (Actually, the statement uses the interesting word, evaculation.) Smith asked Gina if Bernie had put his penie in her mouth. In the words of Smith’s statement: “‘Bernie put his penie in my mouth and it squirted pretend worms in my mouth’. Gina stated that that made her sick when Bernie did this. But that Bernie showed her the mother and daddy worms coming down her face and Gina laughed and felt better.” On October 11, Gina told her mother that the teacher who saw this was not Eileen, the Assistant, but rather Stephanie, the Head Teacher.

Dr. Sheeley, who now practices near Springfield, is well respected. By reputation she is a compassionate and highly competent physician. Sheeley began her practice in Pittsfield in 1982, right after finishing her residency at the Albert Einstein School of Medicine in the Bronx. When she examined Gina Smith, she was relatively inexperienced. But her evaluation was fully consistent with the current medical knowledge at the time. No one had then ever done a study of the vaginas or rectums of non-abused children. It was believed — falsely, as it turned out — that in normal girls the hymen was a flawless membrane containing a small and nearly perfectly circular opening. It was not until 1988 that Dr. John McCann of San Diego’s Children’s Hospital made public the results of a four-year study of hundreds of young children. Hymeneal notches occur in 50-60 percent of non-abused girls. (There was no way, of course, that Sheeley or anyone else could have known this in October of 1984.) According to an insurance-company report, Gina had also been observed inserting objects into her own vagina, subsequent to witnessing the birth of a sibling, and that might have produced the tears. (One wonders what sort of parents would force a two-year-old to witness a birth.)

Gonorrhea?

Sheeley’s worst suspicions about Baran must have been confirmed a day or two later when the results of Peter Hanes’ gonorrhea tests came back. The throat culture was positive. At the time, that was considered proof positive that the boy had gonorrhea. Today we cannot be at all sure, because we now know that the test used at the time had a very high rate of false positives. According to Debbie Nathan and Mike Snedeker, in 1988 “researchers at the federal Center for Disease Control revealed they had tested hundreds of children’s samples sent in by laboratories throughout the country, In more than a third of the samples, the CDC said, the actual organism turned out to be something else.” (Satan’s Silence, p. 195. My emphasis. The authors of the report are W. Whittington et al.)

We can never know whether or not Peter Hanes had gonorrhea in 1984. Given the chaos of his home life, anything is possible. In 1984, the police department and the DA’s office seemed only interested in evidence that could be used against the dangerous homosexual, Bernard Baran. They apparently had little interest in trying to unearth what might actually have been going on. Thus the only professional investigation to date had to wait until Julie Hanes sued ECDC, and the insurance company put a competent investigator on the case. As a result of this investigation, the investigator and the insurance-company lawyers concluded that Peter Hanes had been abused, but by someone other than Bernard Baran. Moreover, they concluded that Julie Hanes knew about the abuse.

What the Jury Never Learned

Before Baran’s trial, according to the insurance-company report, Peter made a spontaneous, detailed and credible disclosure of sexual abuse to a foster mother. (Click here for information about this incident, which came to light during the civil trial in 1995.) DSS interrogated Peter about his alleged abuse by this man (who I will call John Wilson) immediately before the hearing to determine whether he (Peter) was competent to testify against Baran. The DSS investigator concluded that Wilson had been abusing Peter and said so in a report to his superiors filed the day jury selection began in the Baran trial. By law, DSS was required to report the matter to the DA’s office. But incredibly they sat on the information for nine days. On the day Baran was convicted, Regional Director Federico A. Brid finally sent the DA’s office a memo, which was stamped “received” five days later.

John Wilson was a friend of David and Julie’s who moved in with Julie and Peter not long after Julie threw David out — which happened a week or so after Baran’s arrest. (John is the second of Julie’s boyfriends alleged to have stabbed himself in the chest. He also once broke all of the windows in Julie’s car with a pickax.) And according to a sidebar during the trial, Baran’s lawyer, Leonard Conway, said witnesses had overheard a loud argument between the Haneses during which Julie accused David himself of having gonorrhea.

According to Peter’s alleged disclosure, Julie knew that John was sexually abusing Peter. Both Haneses appear to have been very sexually promiscuous. Julie claims she finally threw David out because he was sleeping with Julie’s best friend. She also had David arrested for assault at that time. This incident occurred just a few days after David and Julie went to the local newspaper, The Berkshire Eagle, to be interviewed. During this interview, the Hanes used their actual names and the names of their children. Most parents in their situation would have wished to protect the children’s’ identities. Around this time, the Haneses also met with a lawyer to discuss suing ECDC.

Baran says that during the summer before his arrest Julie’s lovers also included a young man of 15 or 16. (Baran’s lawyer tried unsuccessfully to introduce testimony about this relationship.) According to Baran, Julie even made apparent overtures to Baran himself. And Julie’s sexual relationship with John — whom she had known since childhood — almost certainly predated David’s leaving. If Julie believed her son had been exposed to gonorrhea (perhaps indirectly by David), and if she wanted Peter tested and treated, she may have decided to accuse Baran in order to keep the authorities from finding out what was going on in her own home.

At trial, Conway unfortunately didn’t produce the relevant witnesses nor did he subpoena any supporting medical records. So we may never know what really happened. The foster mother’s questioning of Peter may very well have been coercive and highly suggestive. According to evidence at the civil trial, the foster mother very much disliked Julie Hanes and even wanted to adopt both Peter and his younger brother . She therefore had a strong mother to denounce Julie and John’s household. In short, the foster mother was far from a trained or neutral interrogator.

In any case, if Peter did have gonorrhea, he didn’t catch it from Bernard Baran. When the results of Peter’s gonorrhea test were known, the police immediately arrested Baran a second time. Baran was taken directly to BMC and throat, genital, and rectal cultures were taken. All tests came back negative. No record could be found of Baran having been treated for gonorrhea anywhere. At trial he admitted that four or five years prior, he had been treated for VD, but didn’t know whether it was for gonorrhea. Baran was at that time given a shot, but not of penicillin because he is allergic. Nevertheless, at trial, prosecutor Dan Ford did his best to make Baran’s negative test result count as positive evidence that Baran had had gonorrhea and self-treated it. Ford even had a doctor testify that gonorrhea was most common among prostitutes and male homosexuals, reinforcing the presumption that gay men carry disease.

On 14 July 1988, David Hanes was deposed for Julie’s suit against ECDC. He was asked about the Baran incident. He responded:

It scares me. I don’t know. My brother’s in jail right now for the rape of a child. And I know my brother didn’t do it. I don’t know if Bernie Baran did it. But I know I thought he did at the time. I think I might still think he did it. But I’m not quite sure. My conscience has bothered me a lot. Yeah, I thought about it a lot …. I know on my part exaggeration isn’t the right word. I was getting secondhand information from Julie as to what was going on, and, of course, I believed it.

The following February, David Hanes called up Baran’s mother and said he wanted to talk to her. He was threatening to tell what he knew and blow the case wide open. He called at least one more time, but then got cold feet and would say no more.

The “Investigation”

On Tuesday, October 9, the day before Baran’s second arrest — the Berkshire Eagle broke the news that Baran had been arrested for sexually assaulting two three-year-olds. The article listed a number for concerned parents to call. That afternoon, Steven Thompson called the police. The police report is one very short paragraph that said that Thompson’s son Richard “had been acting strange in the past and at one time mentioned that Bernie touched him in his poo-poo.”

Parents’ meetings were held at ECDC, beginning on October 15, and social workers and police gave out a list of symptoms indicative of abuse. The list that psychotherapist Jane Satullo suggested at trial included curiosity about the genitals, masturbating, inserting things in anus or vagina, bedwetting, soiling, fear of the dark, nightmares, sleeping disorders, eating disorders, becoming aggressive, becoming withdrawn, becoming fearful about a particular person, repeated activity of a sexual nature, removal of clothes, and touching of the genitals. Any child would have at least some of these symptoms.

Arrangements were also made to have all of the ECDC children view a “good touch / bad touch” puppet show. Satullo was one of the people who presented the puppet show to the kids. (These shows were quite common at the time. While they may have flushed out genuine cases of abuse, their highly suggestive content undoubtedly produced many false accusations.) One of the children who saw the puppet show was Richard Thompson. Another was his friend, Johnny Larson, who became another accuser. Richard and Johnny were also interviewed with anatomically correct dolls, and the interviews were videotaped.

The remaining two accusers were both little girls, both of whom were also interviewed with the dolls and videotaped. One was a five-year-old named Virginia Stone (she was the oldest of the accusers), whose mother, Marcia Lopez, was a good friend of Julie Hanes, a prostitute, and a fellow hard-drug user. (Lopez would eventually be arrested on drug charges and sentenced to rehab. She has since died of AIDS.) The first police report on Stone is dated 10/13/84. Lopez called, claiming that Virginia had disclosed that Baran had touched her and put his dinky in her mouth. While Virginia had attended ECDC, at no time had she ever been in either of Baran’s two classrooms. Most probably, Virginia didn’t even attend the facility (Pumpkin Patch) where Baran worked, but rather ECDC’s other facility, Apple Tree. (Stone’s records were very conveniently destroyed in a fire occurring right after Baran’s arrest.) Virginia was taken to Dr. Sheeley, who examined her but found no sign of abuse. Lopez made a statement, saying that Virginia when first questioned denied the abuse, but disclosed it a couple days later. During the videotaping, Virginia said that she didn’t tell because Bernie had said that he would kill her mother. (In real child sexual-abuse cases, this kind of threat is seldom used or effective.) According to the insurance-company report, a few months after the trial, Virginia told her therapist that nothing had really happened, but that her mother had told her to say that it had so that they could get a lot of money. This recantation was reported to DSS, but not to Baran’s attorney.

The final accuser was a three-year-old named Annie Brown. Annie’s mother, Lee Ann Bailey, removed Annie from ECDC when she heard about Baran’s arrest. On Saturday, October 13, Bailey took her daughter to BMC for examination. The following Monday, Michael Harrigan of DSS went to Annie’s house to interview her, and Annie said that Bernie had touched her tuku.

By October 25, all six alleged victims had been identified. Baran’s trial took place three months later, and he faced 12 counts: six of rape and six of indecent assault and battery of a child under 14. Baran was offered a five-year-sentence in exchange for pleading guilty, but he refused.

In preparation for the trial, the children were interviewed and rehearsed by their parents, the police, and social workers. Before the trial began, there were six weeks of mock hearings at the courthouse. (My partner, playwright James D’Entremont, commented, “That’s more time than the Royal Shakespeare Company gets to rehearse Hamlet.”) The Smiths also hired a child psychiatrist, Suzanne King, who saw their daughter once a week. One of King’s beliefs was that children communicated through play, and King interpreted Gina’s play and dreams in addition to talking to the child. Gina’s story became more bizarre.

When Gina had originally said that her vagina had bled, she said that Bernie had cleaned her up with toilet paper. Now Gina claimed that Baran had scraped the blood out of her vagina with a pair of scissors. Baran then supposedly stabbed Gina in the foot with the scissors, making her foot bleed as well. At trial, DA Dan Ford would claim that Baran stabbed Gina in the foot so that the other teachers wouldn’t realize that Gina was bleeding from the vagina. Gina was supposed to have bled, remember, because Baran supposedly penetrated her (a three-year-old) with his erect penis or several fingers. And all of this happened in a bathroom with an open door adjoining a classroom filled with a dozen children and two or more other teachers. Anyone who knows anything about children knows that Gina would have screamed her head off had she had been so savagely raped.

At trial, Dr. Sheeley conceded that such a brutal penetration would be “somewhat painful” for a small child. Sheeley, of course, had examined three of the six children, and in the presence of nearly hysterical mothers who were firmly convinced that their children had been brutally raped by a monster. One of the children had tested positive for gonorrhea. Another had exhibited what at the time was considered positive proof of penetration. One shouldn’t be surprised that Sheeley was less than anxious to say anything that might prove helpful to the defense.

Not one of the six accusers should have been judged competent to give testimony. This is now obvious to any sane person who reads the transcript of the competency hearing, or the actual testimony of the children at trial. (Click here for my notes on the competency hearing.) Given the hysterical climate of the time, of course, Judge William Simons would probably have been lynched had he not permitted all of the children to testify.

The Prosecution

The children were seated on the floor when they testified so that they didn’t have to see the “evil” Bernie Baran. Not only was Baran thus denied his confrontation rights, he couldn’t even see and follow what was going on.

Although the children had been interviewed and rehearsed on a great many occasions by Dan Ford, their parents, the police, social workers, and therapists, the children nevertheless were very poor witnesses. In Court, when they bothered to respond, they shook or nodded their heads, said uh-huh or uh-uh, gave monosyllabic or one-word answers. Whenever a child gave the “wrong” answer, DA Ford just kept repeating the question until he or she answered “correctly.” If a child persisted in not cooperating, Ford would simply ask if the child was scared, and the child invariably responded yes. The clear implication was that the children weren’t testifying because of their terror of the monster, Baran, whom they couldn’t even see. Most of the kids were cooperative with the dolls, however, eagerly poking their fingers into the orifices. Kids get a big kick out of those dirty dolls. (So do prurient adults.)

When Peter Hanes was brought into the courtroom, he broke away and ran over to where Baran was sitting. “Hi Bornie (sic)!” said Peter to his alleged tormentor. When Dan Ford dragged Peter away, Ford said to him, “I know you don’t like Bernie.” Peter replied, “I don’t like you!” and added several choice obscenities. When Ford asked Peter questions on the stand, Peter generally responded with silence.

Peter said he didn’t know Baran, never saw him before. Ford handed him a doll, but Peter showed no interest in it. This led to this exchange:

MR. FORD: After you talk with us you can go back to Macdonald’s. Now show us where Bernie touched you, Peter.

PETER HANES: No.

MR. FORD: Why?

PETER HANES: ‘Cause.

MR. FORD: ‘Cause why?

PETER HANES: I don’t like to.

MR. FORD: Is it hard to talk about this?

PETER HANES: Yup.

MR. FORD: There’s nothing to be scared of, Peter.

MR. FORD: Is that what Bernie did?

MR. CONWAY: Your Honor, I object to this.

THE COURT: Your objection is noted.

MR. FORD: Is that what Bernie did, Peter?

PETER HANES: No,

MR. FORD: What did he do?

PETER HANES: (No response)

While the record doesn’t reflect it, Peter eventually started responding, “Fuck you!” Ford gave up trying to question Peter Hanes. (Click here for Peter Hanes’ complete testimony.)

When Gina Smith was questioned, Ford wanted very much for her to talk about the pretend worms. This led to this exchange:

MR. FORD: Remember something coming out of Bernie’s peniey when he touched you with it?

GINA SMITH: Uh-huh.

MR. FORD: What?

GINA SMITH: Nothing.

MR. FORD: I thought something came out?

GINA SMITH: Nothing came out.

MR. FORD: Mommy, could you just tell Gina it’s okay to tell the truth.

THE MOTHER: What do you think came out?

GINA SMITH: I don’t want to.

MR. FORD: Remember some pretend worms coming out?

GINA SMITH: (Witness nods head up and down)

THE MOTHER: What color were they?

MR. FORD: Mother, you can’t do that.

MR. FORD: Where did the pretend worms go?

GINA SMITH: On my leg.

MR. FORD: On your leg. Anywhere else?

GINA SMITH: (Witness shakes her head from side to side.)

(In Judith Smith’s police statement, the pretend worms allegedly went on Gina’s face.)

When Ford asked Gina if she bled, Gina said “I forget it.” I suspect what she meant was that she forgot the answer she was supposed to give. But after Ford reminded her that she bled, he asked, “What did Bernie do when the blood came out?” Gina answered, “He scooped it out with scissors.” When asked where all this happened, Gina responded, “In my classroom.” The “right” answer, of course, was “in the bathroom.” So Ford then asked, “How about in the bathroom? Anything ever happen in the bathroom?” Gina nodded her head up and down. Ford tried to get Gina to talk about the Bird’s Nest Game, but all Gina would say is “The baby bird got killed.” Ford fell back on his usual tactic of leading Gina to say that the Bird’s Nest Game is too scary to talk about.

Under cross-examination, Gina said that her classmate Eric tied her up with rope and that Eric was in the bathroom with Gina and Bernie. Conway also asked about the bird, but Gina said it wasn’t a real bird, it was a pretend bird. (As previously noted, pretend is one of Gina’s favorite words: pretend police, pretend worms, pretend bird, etc.) Conway asked Gina if Bernie was nice to her in school, and Gina said, “Uh-huh.” On redirect questioning, Gina told Ford that Bernie also cut her hair with the scissors. But she still won’t talk about the Bird’s Nest Game. Upon prodding from Ford again, Gina said it was scary. (Click here for Gina Smith’s complete testimony.)

Richard Thompson and Johnny Larson allegedly were molested together, in a shed at the school and in the woods during a field trip. There was a storage shed on ECDC property, but it was kept locked and Baran had no key. There were no woods on the property, but classes sometimes went on field trips to places like the State Forest. Children of course were always kept together in a group during these trips. And — during the short period of time when Richard and Johnny were in Baran’s room — the only field trips taken were down North Street, a business section of Pittsfield.

While interrogating Richard, Ford asked the boy if Bernie ever played games with him. The boy unhelpfully replied, “Ring around the rosy.” The right answer was “Hide and Seek.” This was their ensuing exchange:

MR. FORD: Did you ever play hide and seek?

RICHARD THOMPSON: Yes.

MR. FORD: Where did you play hide and seek?

RICHARD THOMPSON: Once inside the school.

MR. FORD: Did you ever play hide and seek outside the school?

RICHARD THOMPSON: (Nods head up and down)

MR. FORD: Where did you used to hide?

RICHARD THOMPSON: Shed.

MR. FORD: In the shed. Did Bernie ever find you in the shed?

RICHARD THOMPSON: (Nods head up and down)

MR. FORD: Did Bernie ever touch you in the shed?

RICHARD THOMPSON: (Shakes head from side to side)

MR. FORD: Richard, did you ever see Bernie with his pants down?

RICHARD THOMPSON: (Shakes head from side to side)

MR. FORD: Never did?

RICHARD THOMPSON: (Shakes head from side to side)

MR. FORD: You’re sure? Richard, let me ask you again: Did you ever see Bernie with his pants down?

RICHARD THOMPSON: (Nods head up and down)

MR. FORD: You did?

RICHARD THOMPSON: (Nods head up and down)

Under cross-examination, Conway had the following exchange with Richard:

MR. CONWAY: Do you know what it’s like to tell a story? Sometimes they’re real, and sometimes they’re make believe stories?

RICHARD THOMPSON: (Nods head up and down)

MR. CONWAY: Now, did you tell Jane and the police any stories? Were they real stories or make believe stories?

RICHARD THOMPSON: Fake stories.

MR. CONWAY: Fake stories. Why would you tell fake stories?

RICHARD THOMPSON: (No response).

MR. CONWAY: They kept asking you about it, Hon, didn’t they? And you told them a fake story?

RICHARD THOMPSON: Yes.

(Click here for Richard Thompson’s complete testimony.)

Johnny Larson had difficulty following the script when Ford interrogated him. For example:

MR. FORD: Did you ever see something come out of Bernie’s dinky?

JOHN LARSON: (Nods head up and down)

MR. FORD: What?

JOHN LARSON: Nothing.

MR. FORD: Nothing came out?

JOHN LARSON: Uh-uh.

MR. FORD: Did something white come out?

JOHN LARSON: Uh-uh.

MR. FORD: Something yellow come out?

JOHN LARSON: No.

MR. FORD: Nothing at all? Did something from Bernie’s dinky ever go on your face?

JOHN LARSON: Uh-uh.

MR. FORD: Did it go somewhere else?

JOHN LARSON: Uh-uh.

(Remember, uh-uh means no and uh-huh means yes.)

Ford also led the boy into testifying that Baran told him scary stories about wolves, and devils, and fire. Under cross examination, Johnny said that this was the story about the Big Bad Wolf and the Three Little Pigs. Johnny also said that sometimes he makes up stories and tells them.

(Click here for Johnny Larson’s complete testimony.)

Virginia Stone was most uncommunicative in court. She often didn’t respond to questions, or responded by nodding or shaking her head. She didn’t respond when asked by Ford, “did Bernie ever touch you somewhere?” and “Show us where Bernie touched you.” But she pointed to the expected place when Ford gave her the anatomically correct doll. And she said, “In my mouth” in response to, “Tell us where Bernie put his dinky.” Under cross-examination, Virginia admitted that she has talked about this to her mother and to Dan Ford many times before. She said that she had talked to Ford eight times. Under leading questions from Ford on redirect examination, Virginia said that Baran said he’d kill Virginia’s mother if Virginia ever told.

(Click here for Virginia Stone’s complete testimony.)

Annie Brown was barely three and the youngest of Baran’s accusers. She was also the least competent to testify. Reading her testimony at trial and at the competency hearing, one quickly realizes that the poor kid had no idea whatsoever about what all the crazy adults around her were doing. All of the children at this trial were giving a simplified oath: Do you promise to tell what happened? But the first time Annie was called, neither the Court, the Clerk, nor Ford can get her to say yes to the question. Finally, they give up and decide to try later. Shortly after this, Baran’s sister overhears Ford telling Annie in the hallway, “Just say yes to the questions and then we can go to MacDonald’s.” Conway complained about this in the judge’s chambers, but Ford said he was merely trying to convince Brown to take the oath. Conway said that if it took that much effort to get her to say yes to such a simplified oath it seriously called into question Annie’s competency to testify. This did not please Judge Simons, who said, “I have considered very carefully this issue of competency with regard to each one of these children separately.”

On the second attempt to elicit testimony, Brown finally nods her head when given the simplified oath. Her questioning by Ford was as follows:

MR. FORD: Angie, did you ever go to school at E.C.D.C.?

ANNIE BROWN: Yes.

MR. FORD: Did you have some teachers down there?

ANNIE BROWN: Bernie and Stephanie and Eileen.

MR. FORD: Bernie and Stephanie and Eileen?

ANNIE BROWN: Yes.

MR. FORD: Did you like it down there?

ANNIE BROWN: (Nods head up and down)

MR. FORD: Did Bernie ever touch you while you were down there, Angie?

ANNIE BROWN: No.

MR. FORD: He never touched you?

ANNIE BROWN: I didn’t see him touch you.

MR. FORD: You didn’t see him touch you?

ANNIE BROWN: He was just pretending.

MR. FORD: He was what?

ANNIE BROWN: He was just pretending.

MR. FORD: Oh, he was pretending to touch you? Oh, let me take this dolly right here. Can you show us where Bernie pretended to touch you?

ANNIE BROWN: Okay. Right in here, all the way in.

MR. FORD: All the way in there?

ANNIE BROWN: Yes.

MR. FORD: May the record show the witness put her finger in the doll’s opening.

MR. FORD: Is that the way Bernie touched you?

ANNIE BROWN: Yes.

MR. FORD: Were your pants up or down?

ANNIE BROWN: Up.

MR. FORD: How did he do it?

ANNIE BROWN: Like that, with his hand.

MR. FORD: Did he put his hand inside your pants?

ANNIE BROWN: Yes.

MR. FORD: He did. What room were you in, Angie?

ANNIE BROWN: I was in room #4.

MR. FORD: Room #4. What part of room #4?

ANNIE BROWN: (No response).

MR. FORD: Do you know what part? Was this the classroom or the bathroom or the nap room?

ANNIE BROWN: The classroom.

MR. FORD: How did that make you feel, Annie, when Bernie –

ANNIE BROWN: That made me feel sad.

MR. FORD: Now, Annie, see this man right here?

ANNIE BROWN: (Nods head up and down)

MR. FORD: His name is Mr. Conway. He’s a very nice man and he’s going to ask you a few questions too, and I want you to answer him just the way you answered me. Okay?

ANNIE BROWN: Yes.

MR. FORD: Thanks, Angie.

Under cross-examination, Annie said that she likes Bernie, she still liked Bernie, and that Bernie was a good boy. (Later, she changed her mind, and told Conway that she doesn’t like Bernie.)

(Click here for Annie Brown’s complete testimony, including the first attempt to administer the oath.)

In addition to the children, the main witnesses for the prosecution were the parents, police, DSS workers, and therapists. The parents were probably most compelling. The parents of at least four of the six children sincerely believed that Bernard Baran had done horrible unspeakable things to their three- and four-year-olds. They probably still feel that way today. And the children involved in this tragic case almost certainly sincerely believe that Bernard Baran horribly abused them. The memories implanted within them during the investigation are there to stay.

An important prosecution witness was psychotherapist Jane Satullo from the Rape Crisis Center. Satullo was one of the people who performed the “good touch/bad touch” puppet shows, and also interviewed several of the children using anatomically correct dolls. As professional influences, Satullo cites works by Suzanne Sgroi and Nicholas Groth. ((Transcribed by the court reporter as Susan Savoy and Nicholas Brown. Sgroi developed the child-sexual-abuse syndrome, very similar to Dr. Roland Summit’s child-sexual-abuse-accommodation syndrome. Sgroi and Groth wrote books together, and once co-edited a book with the previously mentioned Ann Burgess. Research has not validated their theories. During the 90s, Sgroi also pointed out that her theories were being misunderstood and misapplied, and she was even helpful to the attorneys working on Margaret Kelly Michaels‘ successful appeal.) When testifying, Satullo dismissed the idea that her puppet show could “plant an idea concerning abuse in a child’s mind.” Satullo also said that “any child who is able to tell a story and repeat its details over a period of time then there is validity to that story” and “It’s hard enough for adults to repeat a story with details. It really is impossible for a child to do that.”

Under cross-examination, Satullo is confronted with the fact that the children’s stories haven’t been consistent, that details changed over time, and that some of the details were almost certainly false. Satullo is not fazed. Children provide more details as they become more relaxed. The fact that a child mentions one teacher in a story one time and a different teacher another time, only demonstrates the “general interchange that adult roles play in the child’s life.” Satullo baldly states “there haven’t been any cases of children falsely accusing somebody” and that children are “no more susceptible than the rest of us” to suggestion.

Dr. Suzanne King, the child psychiatrist who had been seeing Gina Smith, provided similar testimony. King was the therapist who believed that children communicated through their play, and she said that the themes of Gina’s play “have had to do with fear from bad men, with being injured, and with the need for safety and protection.” King insisted that these things couldn’t be the result of the power of suggestion. King said that Gina’s resumption of bedwetting was a symptom of sexual abuse, and that a child Gina’s age couldn’t make up a story about sexual abuse. (Gina, of course, had lots of help from adults in creating her bizarre abuse story.) Under cross-examination, King conceded that one might be able to suggest a fact to a child, but that one couldn’t suggest the feeling or anxiety that goes with it. She stated that a parent’s anxiety was not transferable to a child! (One wonders if King at this point in her life had ever encountered a real child in the real world, as opposed to the artificial world of the therapist’s office.) King also conceded that her interpretation of a child’s play was a subjective, not an objective process. “I would never make an interpretation without some sort of history,” she admitted. (In other words, King’s interpretation of Gina’s play assumed Gina had been abused.)

The notion that children weren’t suggestible — especially when it came to accusations of sexual abuse — was standard among psychotherapists of the early 80s. Since then, much work has been done on the question by Stephen Ceci, Maggie Bruck, and other researchers. What they discovered was that children are highly susceptible to suggestion — especially children as young as those involved in the Baran case. Responsible therapists and investigators have put away their puppets and their anatomically correct dolls and have learned how to get reliable information by asking open-ended questions, by avoiding repetitive questioning, and adopting other approaches suggested by current research. (Many, unfortunately, insist on clinging to the old methods, and many false accusations still result.)

Most parents, of course, have always known that children are impressionable and suggestible from their own experience. Even Judith Smith, in her police report, stated that she had put Eileen’s name into Gina’s head as the person who had witnessed Gina’s abuse. It’s very easy to put information into children’s heads. If it weren’t, kids wouldn’t be teachable. And regardless of what Dr, King says, those of us who’ve spent time around kids — or who at least remember what it was like to be a kid — know that kids readily absorb their parents’ anxieties, fears, and prejudices. (My lifelong fear of snakes is totally irrational. I got it from my mother, and not from anything that she ever said.)

The other prosecution witnesses were school employees: teachers and Janie Trumpy, the Executive Director. The teachers, who knew Baran well, gave little help to the prosecution. They not only believed Baran incapable of such horrors, they also realized the impossibility of committing them undetected at an open facility like ECDC. (Trumpy assumed her position at ECDC in mid-September, just a few weeks before Baran’s arrest.) The teachers testified that they had never observed any suspicious behavior between Baran and any child. A great deal of courage was required for the teachers to do this. Eileen Ferry, for example, told Baran’s mother that she had to distance herself from them because Dan Ford had darkly hinted to her that he might just “expand” his inquiry if the teachers were too cooperative with Baran’s defense.

After the prosecution rested, Judge Simons threw out three charges: the two charges concerning Peter Hanes and the rape charge involving Johnny Larson. Simons also decided that the jury could convict on one, but not both, of the charges concerning Annie Brown. Thus the twelve charges were reduced to a maximum of eight.

While most of the parents sincerely believed that Bernard Baran had molested the children in his care, we can be much less certain of prosecutor Dan Ford. After the prosecution rested, Ford repeated his offer of a five-year sentence in exchange for a guilty plea. Moreover, Baran could serve half the time at the county jail and the other half at a low-security facility called the Sheriff’s Home. If Baran refused, Ford would ask for consecutive sentences to insure that Baran never got out of prison. Baran refused, and the ambitious prosecutor kept his word.

While we don’t know whether or not Prosecutor Ford believed Baran guilty, we do know for certain that Ford despised gay men. For example, Ford intimidated Baran’s boyfriend, threatened him also with prosecution, and repeatedly called him a “fag.” Ford also illegally told Baran’s boyfriend that he was not allowed to speak with anyone else, including Baran’s attorney. (We are quite certain that Ford unethically intimidated other potential witnesses for the defense as well. And if threatening, abusing, and inflicting homophobic slurs upon a potential defense witness to insure silence does not constitute gross prosecutorial misconduct, then the term has no meaning. For, more information, see this affidavit.)

The Defense

Baran’s defense occupied just one day of the trial, and Baran was the principle witness. Conway also called Richard Herdman, the custodian who found the dead bird in the bathroom; the two teachers that Baran had worked with most closely; Baran’s sister, for whom Baran frequently baby sat; and Dolly Haywood, a friend of Baran’s. (Baran used to go over to Dolly’s house every lunch hour to eat and to watch Days of Our Lives with Dolly. Ford had tried to put as sinister an interpretation as possible on the fact that Baran that summer had frequently come to work early. Ford implied that Baran wanted to spend every possible free moment around the children, alert for an opportunity to rape them. The actual reason Baran came in early was that the school had placed him on probation for too often coming in late.)

Given the dreadful trauma he had suffered, Baran appears actually to have been a good witness. He explained in detail his schedule at ECDC, making it obvious that he had no opportunity to molest the children. He denied having sexual contact or engaging in behavior that might have been interpreted as sexual with the children.

During Baran’s cross-examination, Ford prodded Baran about his relationship with his boyfriend. He repeatedly asked Baran whether he liked children, whether he enjoyed working with them. He asked Baran whether he can say with absolute certainty that in 2 1/2 years he was never alone with a child, and Baran, of course, could not. When Baran explained that he started coming in early after being placed on probation because he didn’t want to be fired, Ford came back with “because you liked working there at that day care center with those little children.”

At no time during the trial did Dan Ford ever demonstrate a motive on Bernard Baran’s part. Baran is not now nor has he ever been a pedophile. Nothing in his history suggests this, and he has always convincingly denied it. But he is a gay man. And he did like children. And that was all that Dan Ford needed to make clear to the jury.

The Conviction

Ford outdid himself in his closing statement to the jury. He began by praising the jurors, and singing a hymn to the jury system, “the best system known to the civilized world for ascertaining the truth in criminal cases.” Ford humbly said that nothing Ford “could say could possibly be as persuasive or as convincing as the testimony of those little children who testified before you over the course of this trial. I dare say that the great Clarence Darrow himself would pale in comparison to them.”

Ford reminded the jury of the testimony of the parents, of the “experts” Suzanne King and Jane Satullo who had testified that children are not suggestible. Ford stated that Baran had plenty of opportunities at ECDC, and said “he could have raped and sodomized and abused those children whenever he felt the primitive urge to satisfy his sexual appetite.” Ford likened Baran to “a chocoholic in a candy store.”

Ford explained to the jury why Gina Smith — who allegedly had been brutally fully penetrated, which caused her vagina to bleed, and then stabbed in the foot with a pair of scissors — hadn’t screamed out at the time nor ever disclosed what had happened to her to any adult. It was because of the Bird’s Nest Game. Ford said: “if she told anybody about what Bernie did to her the baby bird’s mother would be taken away by the pretend police and the baby bird would be hurt. That one frightened Gina so much she couldn’t even tell us about it here in court. She could talk about being raped, she could talk about being sodomized but she wouldn’t repeat the bird’s nest story. That’s how much that one scared her.”

The jury spent 3 1/2 hours to find Baran guilty on all counts. Baran received a fair trial in the sense that black men accused of raping white women in Mississippi during the 1930s received fair trials. It was the nation’s first daycare case conviction.

Before sentencing, victim-impact statements were given to the Court by two genuinely grief-stricken parents, James Smith and Donna Thompson.

But one of the most dramatic moments of the trial occurred when an ECDC parent, Mrs. Melinda Ward, pled for Baran. Ward was one parent who had not fallen victim to the hysteria. She told the Court:

Bernie came into my son’s life — my son was very young. When he started to attend ECDC it was groans and no communication and he couldn’t get along with anybody. That so-called monster started my son on the path of a normal childhood and taught him — taught my son how to interact with other children and encouraged my son to learn and he just became a miracle worker. He filled something that Dougie needed very much.

Now, there’s no two people in the world that I love more than my son and daughter. I would entrust my life and the lives of my children with that man. I just can’t believe that Bernie isn’t entitled to a little compassion and fairness and dignity above all else. That man gave my —

At this point, Conway asked about Dougie’s reaction to Bernie since everything has been going on. She replies:

He misses Bernie very much and when I told him — I kept him in the dark about everything. He still doesn’t know what’s going on with Mr. Baran. But when I told him I was going to be seeing Bernie he picked out a photograph in the book. He wanted me to give that photograph to Bernie even though it was a year old — give it to Bernie because he had his best suit and bicycle, because Bernie had encouraged him to ride and to do things and he wanted to see Bernie very much and he still does.

I encourage any contact between my son and Mr. Baran because he’s not the monster people have made him out to be.

Dan Ford asked Simons to impose two consecutive life sentences, to insure that Baran wouldn’t be eligible for parole for at least 30 years. Baran was instead sentenced to three concurrent life sentences, which he continues to serve. (Click here for Baran’s description of what it is like to enter Massachusetts’s Attica.) Parole is not a possibility, because innocent people are not eligible for parole. Though the years, Baran has steadfastly proclaimed his innocence.

Since the Conviction

Unlike some of the other defendants in the 80s daycare cases, Baran had no money for an adequate defense. His mother’s only asset was her car. Conway had asked for a $500 retainer fee and, after losing the case, never sent her another bill. Baran’s mother and Baran’s boyfriend — who had recently received an insurance settlement — raised $10,000 between them. This is not much for an appeal, but it was all they could afford. Leonard Cohen handled the direct appeal, but his associate, David Burbank, did most of the work. The grounds for the appeal were than the children weren’t competent to testify, that the indictments should have been separated, and that no Bill of Particulars had been presented. On March 28, 1986, the Berkshire Eagle reported that Baran’s conviction had been upheld by the state Appeals Court. On June 4, 1986, the Eagle reported that the Supreme Judicial Court had refused to hear Baran’s appeal.

In May of ‘84, Virginia Stone’s mother sued ECDC for $750,000. Julie Hanes, in July, sued for 3.2 million. The lawsuits were eventually combined, but didn’t come to trial until 1995. By this time, Virginia’s mother had died of AIDS and Virginia had become a foster child. A lawyer subtly conveyed the message to Baran that if he would just say that he had actually molested Peter Hanes, Baran would receive a lot of money. Baran reported this attempted bribe to Jocelyn Sedney, one of the lawyers for ECDC’s insurance company. The dishonest lawyer denied everything and accused Baran of making the story up. Before the trial began, Virginia Stones’s lawyer discovered that Stone had recanted her accusation and settled for a small amount. Julie Hanes persisted in her scheme for a multi-million dollar settlement, but the insurance company lawyers demolished her credibility under cross-examination. Her lawyer offered to accept a small settlement to end the trial, and the insurance company lawyers accepted.

The Smiths subsequently divorced. James Smith was awarded custody of the children.

Melinda Ward, I’m sorry to report, is recently deceased.

Peter Collias, one of the main detectives in the Baran case, went on to become a zealous crusader against child sex abuse. He cofounded Citizens Against Child Abuse, has interviewed hundreds of children, and has testified repeatedly in court — not always accurately, according to supporters of some of the other people Collias helped convict. Eventually Collias “recovered” his own memories of abuse. An idolizing story about Collias in the Boston Globe (10/13/96) stated that Baran had been “accused, and later convicted, of molesting 25 toddlers.”

Daniel Ford is no longer a prosecutor. In April 1989, Massachusetts Governor and failed presidential candidate Michael Dukakis appointed Ford a Superior Court Judge. He remains on the bench today.

Bernard Baran is a small person, who weighed less than 100 pounds at the time of his conviction. In prison, he has suffered unspeakable physical, emotional, and sexual abuse —` abuse that he finds almost impossible to talk about today. His first rape occurred just four days after he was sent to Walpole. Over the next four years, he would be raped and beaten 30-40 more times. He has suffered serious eye injuries and many broken bones. He has been shuffled around the Massachusetts prison system. He was sent first to Walpole, then to Concord, then to Gardner, then to the Southeast Correctional Center, then to Norfolk, then to Old Colony, and finally to the Bridgewater Treatment Center, where he resides today. Baran wanted to get into Bridgewater because he knew he would be relatively safe there. But to get in, he had to be civilly committed, from one day to life, as a sexually dangerous person. Not wanting to admit guilt for things he hadn’t done, Baran told Dr. Ungerer, “I think I could benefit from going to the Treatment Center because of questions about my sexuality.” (Ungerer claims, in his report, that Baran admitted his crimes. Baran denies this. But Ungerer was hardly an attentive interviewer. At one point during the interview, Ungerer actually fell asleep.) At Bridgewater, Baran had a good relationship with therapist Debbie Diamond, who believed in Baran’s innocence. Debbie left her position in December 1998. Baran’s current supervisor is Tim Sinn, who believes that anyone who claims innocence “is in denial.”

For the past 16 years, Bernard Baran has been a forgotten man. Partly because he is gay, he has never attracted the support that has benefited many of the falsely accused families. And because he has been convicted (although falsely) of sexually abusing children, gay leaders shun him because they fear accusations of condoning sex between adults and children. The only journalist who has ever investigated this case — David Mehegan of the Boston Globe — did a biased and sloppy job. When I visited Baran for the first time, I asked him about visiting rules. “I don’t really know much about them.” He said. “No one ever comes to see me except my mother.”

But from time to time, someone has stumbled upon his case and has wanted to do something to bring this horrible miscarriage of justice to an end.

One such person was Jocelyn Sedney, one of the lawyers for ECDC’s insurance company during the Stone-Hanes civil suit. Sedney, along with the insurance company investigator (a tough ex-cop named Johnson) became convinced of Baran’s innocence. Sedney helped Baran find a pro bono attorney, John Andrews of Salem, who took Baran’s case for a while. Andrews, unfortunately, was unable to follow through on his promise to help Baran.

Another person who stumbled upon the case was my friend Debbie Nathan, co-author with Mike Snedeker of the best book about the 80s daycare panic, Satan’s Silence. I knew Debbie because we have both been active within the National Writers Union. Debbie was unable to delve very deeply into the case, but she remembered that it was the first daycare conviction in the nation, and she had been repelled by the blatant homophobia evident during Baran’s prosecution. Nathan, until very recently a reporter for the San Antonio Current, has never been in a position to adequately cover the case. But she has never forgotten it.

Another person who found out about the Baran case was Jonathan Harris, who at the time was a professor at MIT. Harris had done very important work in researching and reopening the Fells Acres, or Amirault, case. In addition to the Fells Acres material, Harris placed information about Bernard Baran on his web site. I think I first found out about Baran through Harris’s web pages.

In June of 1998, after Judge Isaac Borenstein awarded Cheryl Amirault a new trial, Debbie began to prod me to investigate the Baran case. At that time I was reluctant to do this, as I was awaiting the final resolution of Fells Acres. But Debbie was persistent and gave me Baran’s mother’s home phone number. I finally called her. My conversation with Bertha was distressing, because I realized that she had more or less given up hope. But she still deeply loved and believed in her son. She gave me Baran’s address, and I finally wrote to him for the first time on August 31, 1998.

On 3 June 1999, I finally went out to Bridgewater to meet Bernard Baran. I liked him very much, but observed that he was very nervous and probably a bit distrustful. For a few months after that visit, I kept in touch with him by phone and mail. That fall, I re-encountered an old friend, Richard Callahan, who long did prison ministry as a Quaker. Richard became interested in Baran’s plight and he now brings me and my partner, Jim D’Entremont, out to see Baran once a week. All three of us have come to love and treasure Bernard Baran very much — he’s an incredibly brave and sweet person.

Eventually, the Committee for Public Counsel Services appointed Boston Attorney John Swomley to represent Baran. John is bright, passionate and compassionate, and a true friend of the friendless. Swomley is one of the few public defenders willing to defend accused sex offenders, and, as a result, has a number of clients at Bridgewater.

Swomley is not an appellate attorney. But he has found an experienced and highly competent out-of-state trial and appellate attorney to prepare a new-trial motion. Many of the best and most experienced lawyers in the nation are now aware of this injustice, and we may make use of their knowledge in the future. When a new trial is ordered, Swomley will defend Baran.

Baran is in fairly good physical shape. He is slight and although he now weighs about 150 pounds, he is by no means overweight. A few years ago, he had a nasty bout with pneumonia and had to take steroids for six months to rebuild his lungs, which are still very fragile. His hairline is receding, but he still looks remarkably boyish. (At the time of his trial, his newspaper photos made him look about 14.) Over sixteen years of cruel mistreatment have understandably damaged his spirit, but he remains essentially a gentle and good-hearted person. Bernard Baran is a person I would be proud to have as a brother, a nephew, a son.

Baran finds writing difficult, but on March 3, 1999, he wrote me a letter that moved me very much. I’d like to share the beginning of that letter:

Dear Bob,

I was so happy to hear from you. I did receive your letter with the web site papers in it and I liked it very much. I would like to thank you for the time you have put forth in my behalf. I would also like to tell you that I’m very sorry for not writing you sooner. I just at times get so down in the dumps I find myself fighting just to get out of bed and keep going.

I was talking to my mother last night and as we talked I started to cry. I just told her I don’t know how much longer I can hold on for. I have spent 15 years of my life locked away for something I never did and after a while you start to lose all hope. I tell you this because when I see your letter that’s what I start feeling is hope and it scares me.

I don’t even know if I should have told you that but it’s the truth. At times Bob I feel so all alone. I also do believe people have tried to help me but life moves so fast out there that I seem to always get lost in the process. I’m not saying that you would do this to me. It’s just how it has gone so far. So I fear the hope others bring into my life because I’m always left alone in the pain. My heart can only take so much pain. I’m sure you know that a lot of pain comes from inside as well. I’m glad I started this letter to you. I have wrote to you maybe 10 times already, I just never mailed them out. And believe me this one’s going.

For 16 long and lonely years, Bernard Baran has been lost in the process. I can only agree with the late Melinda Ward: Bernard Baran is “entitled to a little compassion and fairness and dignity.”

-Bob Chatelle, 12/3/00

Note: Sources for this background document include Baran’s trial transcript, the transcript of the 1995 civil suit, police reports and parents’ statements, interviews with Bernard Baran, and articles in the Berkshire Eagle. Two books that provided essential background information were Satan’s Silence, by Debbie Nathan and Mike Snedeker (New York: BasicBooks, 1995) and Jeopardy in the Courtroom, by S.J. Ceci and M. Bruck (Washington: American Psychological Association, 1995).